Estimation v. Prediction: An Overview

A look at how classical statistical approaches differ from their new-age cousin.

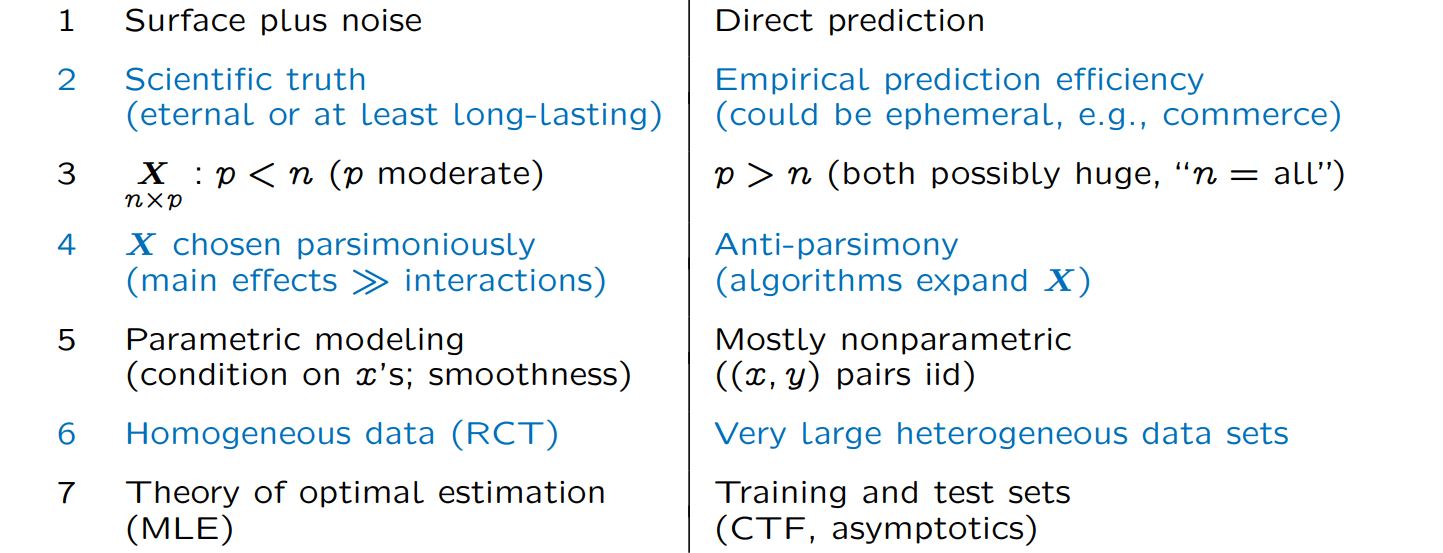

As any helpful (or preachy) soul would happily remind you, it's critical to review the concepts that you've been introduced to -lest you forget. So, that's exactly what I did with Professor Efron's lecture titled Prediction, Estimation, and Attribution. Image above is a slide that he used to wrap up the bulk of the materials that he had been sharing, so it's only appropriate that we start from there.

If you have not yet, please consider going through my original post on my takeaway's from his lecture. Otherwise you may find this post confusing and/or underwhelming.

Going right into the topic, how exactly are the two different approaches different? They are both statistics, so how can they really be all that different? Turns out, the difference can be quite drastic.

The first thing to consider is the underlying objective of the modeling/algorithmic procedure. Estimation algorithms work with a critical assumption: There is a (smooth) surface, the representation of the scientific truth, that is blanketed by the chaotic noise of the world. All the effort is focused around getting to the core of this surface, ultimately uncovering the scientific truth; a rule in which this universe is run. In comparison, prediction algorithms, true to their name, only focuses on exactly that -prediction. The thought is to throw every little thing that we know that connects to the value that we want to find (and sometimes this connection is a stretch) in order to find get the closest prediction possible. To achieve this, data scientists and machine learning engineers are very comfortable with using ephemeral data that inevitably requires an update. Often, it is in my experience that the model that is created is only relevant until the next batch of data. Most of the major differences in the algorithms stem from these differing perspectives and approaches.

Take the data, you'll notice that classical statisticians use very carefully selected features, or p, and almost always end up having more observations of the data, n, than there are features. This is very intentional, any model will get more accurate if you throw more data in order to build it, but it also increases covariability. This means, in the practical sense, that we now know less about how the individual features contribute to the model -something that is absolutely critical when you are trying to 'uncover the hidden surface'. However, modern-era prediction algorithms often have a gigantic number of features. So gigantic, in fact, that is typically incomprehensable for the human mind to process. It is also quite common that the algorithm will continue to build more features on top of the ones that are collected in order to increase the predictive power. This isn't to say that the number of observations that the prediction algorithms are not huge in their own right (they also are), but that the prediction algorithms are characterized by their indifference to increasing covariability. This also makes sense: they are not trying to understand the features better, the only concern is to build the most powerful predictive model.

In a sense, it really is a shifting slide that is within the architect's control. Estimation algorithms force the statistician to be stingy with the number of features. More features mean that you can paint a more holistic picture, and you certainly do not want to leave out any features that may have been critically related to the underlying surface. However, more features also mean that you have a more murky picture of how things are connected with each other, on what things really matter. If you start shifting slide all the way to the other side, you can see the engineer's perspective. An engineer doesn't necessarily care about the underlying truth, you as an engineer want things to work, and to work as accurately and precisely as possible. So you throw everything that you have against the problem of prediction, and you start worrying more about things like the overall size of the data, how long it will take to process and build the model, or how much computing power that you have.

This perspective also impacts what kind of data is being collected. Statisticians want things to be as homogeneous as possible so that the truth is easier to find. The data should be collected from a closely related situation, ideally from a controlled but randomized sample of people. Engineers, on the other hand, are not restricted by the desire for homogeneity. By sacrificing interpretability, they create prediction algorithms that are much more applicable. The goal, if possible, would be to collect information from the entirety of the population, not just a miserly sample.

Ultimately, statisticians turn to the theory of optimal estimation that have been optimized over the course of the century, with tried-and-true maximum likelihood estimation playing a central role. Engineers replace this mathematically optimized theory instead with training and test sets, making the data that is collected their guide towards their objective. This by no means is a weakness -and if it feels like I'm implying that it is, I have been doing a poor job. It does what it intends to with incredible performance. However, the lack of firm theoretical structure makes it so that any new method that boast high predictive power is difficult to scrutinize scientifically; "good prediction" as a concept becomes more subjective, and no one algorithm can be truly leaned on.

There is a new boom in the field of statistics and analytics, and I believe we would all be wiser to adopt a dual perspective. It is noting short of a waste of time to criticize one method over the other. Instead, we should understand the underlying goals of what the algorithms try to achieve, and be able to prepare ourselves that we can utilize the one that the situation that we are in calls for. Not only that, but we should also take advantage of this new era to uncover more varied, more powerful methods that give us a better understanding of this world.

With that hope for the future, I'll close this post.